Late Antique gravestone from Gosposvetska Street

From Museum Treasury

From the first third of the 4th century CE to the early part of the 5th, there was a cemetery beneath present-day Gosposvetska Street, to the west of the main northern approach road to the Roman Emona. The cemetery had grown up around a structure that contained a number of graves and that had been built there in the second half of the 3rd century. The oldest of these graves, which are probably early Christian, was of a woman and contained a blue glass bowl.

Emonan Christian cemetery

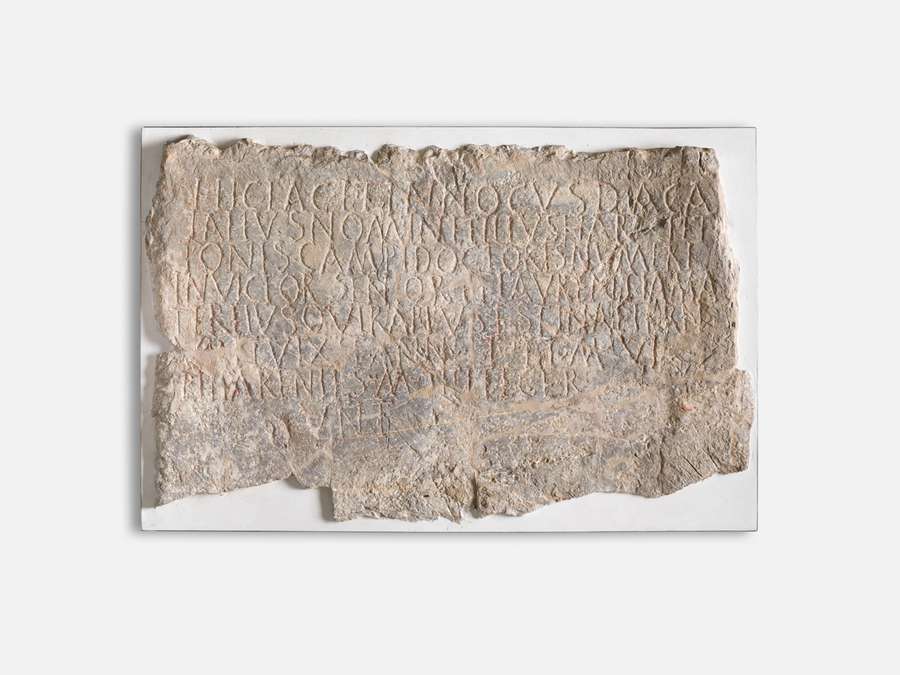

Archaeological research carried out during the most recent renovation works in Gosposvetska Street in June 2018 yielded a Roman stone slab with a Latin inscription. It had been used to mark a small stone funeral casket that contained the poorly preserved remains of the skeleton of a child. At the time of burial, the casket was first covered with earth and then 11 coins were added as an offering. Mortar was then poured over its surface, and a stone slab placed on top of it. The slab carried an inscription in red (the remains of the red paint are still visible today). Judging by the coins, the grave can be dated to the last quarter of the 4th century or the early part of the 5th.

The grave was situated in the southern part of a more recent building erected immediately above the original structure, and which must have been the cemetery church. The fact that the child was buried inside the church, where space would have been scarce by the turn of the 5th century, is indicative of special status or parental influence. A similar slab, discovered during construction of a nearby sewer in 1892, was dedicated to two children, Ioannes and Marcellinus, by their grieving parents, Marinus and Ursa.

The inscription on the slab from Gosposvetska Street was originally created in red in order to make it stand out. The remains of the paint have been preserved. The inscription reads:

Hic iacet innocu(u)s Daga-

laifus(?) nomine filius Har[[ịẹ]]iet-

tonis campidoctoris numeri

invictor(um) senior(um) et Laurentia ma-

ter (!) eius qui raptus est in aetern-

um ẹt vixit ann(os) II et m(enses) VI

pii parentes m(emoriam) illi fecer-

unt.

Translation: Here rests an innocent (child) named Dagalaifus (?), son of Harietonis, a drill instructor in the invicti seniores, and mother Laurentia, taken into eternity after living for two years and six months. This monument was erected by his devoted parents.

What does this funeral inscription tell us?

The slab had been commissioned by the parents (mother Laurentia; father Harietonis) of a young boy called Dagalaifus (the inscription is barely legible here, so the name may not be correct), who had died before he was three years old. They are all shown with only one name, as was customary in Late Antiquity. The mother’s name, Laurentia, was extremely popular with both Christians and pagans during the rise of Christianity, and it became even more common after the death of Deacon Laurence, who was martyred during Emperor Valerian’s persecutions of the Christians in 258. The names of the father and son are of Germanic origin. The name Dagalaifus features prominently on monuments from the 4th century.

A story of a Roman soldier

Dagalaifus’ father Harietonis was a campidoctor, a man trained to drill soldiers in a military camp. He would have occupied a high position in the military hierarchy, immediately below the six centurions. His unit, the numerus invictorum seniorum, is mentioned in the 5th century Notitia dignitatum as one of the army units of the Late Antique Roman Empire. Dagalaifus’ gravestone is the first instance of this army unit being documented epigraphically, i.e. as part of an inscription on stone, wood or other similar material.

Harietonis’ unit might have been stationed in Concordia (Iulia Concordia; now Concordia Sagittaria) in northern Italy. A large number of gravestones dedicated to members of Late Antique military units who had fought with Emperor Theodosius (379–395) in the 4th century have been discovered there.

Colophon

.

Epigraphic expert opinion and interpretation by:

Honorary Prof. Dr. Ioan Piso, Facultatea de Istorie şi Filosofie, Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai, Cluj-Napoca

Anja Ragolič, ZRC SAZU, Institute of Archaeology