Footnotes

[1] Grabrijan, Plečnik in njegova šola / Plečnik and His School, p. 8. This book also contains Plečnik's thought taken as the title of this article.

[2] Helena Molka (1831–1899), married Plečnik; her son Jože respected her very much and was extremely attached to her.

[3] Otto Wagner (1841–1918) was an Austrian architect, urban planner and theoretician; in 1894 he became a professor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and is considered one of the pioneers of modern architecture.

[4] Adolf Loos (1870–1933), an Austrian architect of the Czech origin, an influential European theoretician of modern architecture, Plečnik's contemporary.

[5] "Nicht dem Quadratmeter Zeichenpapier, sondern dem Menschen Pletschnik [sic] wurde der Preis [Rom-Preis der Akademie der bildenden Künste, Wien] zuerkannt. Und das ist ein höchst seltener Mensch, ein Mensch, der die italienische Luft nöthig hat wie einen Bissen Brot. Denn Pletschnik ist der hungrigste unter unseren jungen Architekten. Deswegen muß man ihm auch zu essen geben. Des Einen sind wir gewiß: Was er auch immer verbraucht, er wird es uns tausendfach an Kraft zurückgeben."

Adolf Loos, Aus der Wagnerschule. Neue Freie Presse, 31. 7. 1898, p. 12.

[6] Hrausky, Koželj, Maks Fabiani, Ljubljana 2010, p. 21.

[7] Maks Fabiani (1865–1962), an architect of Slovenian origin, urban planner, professor, innovator and theoretician.

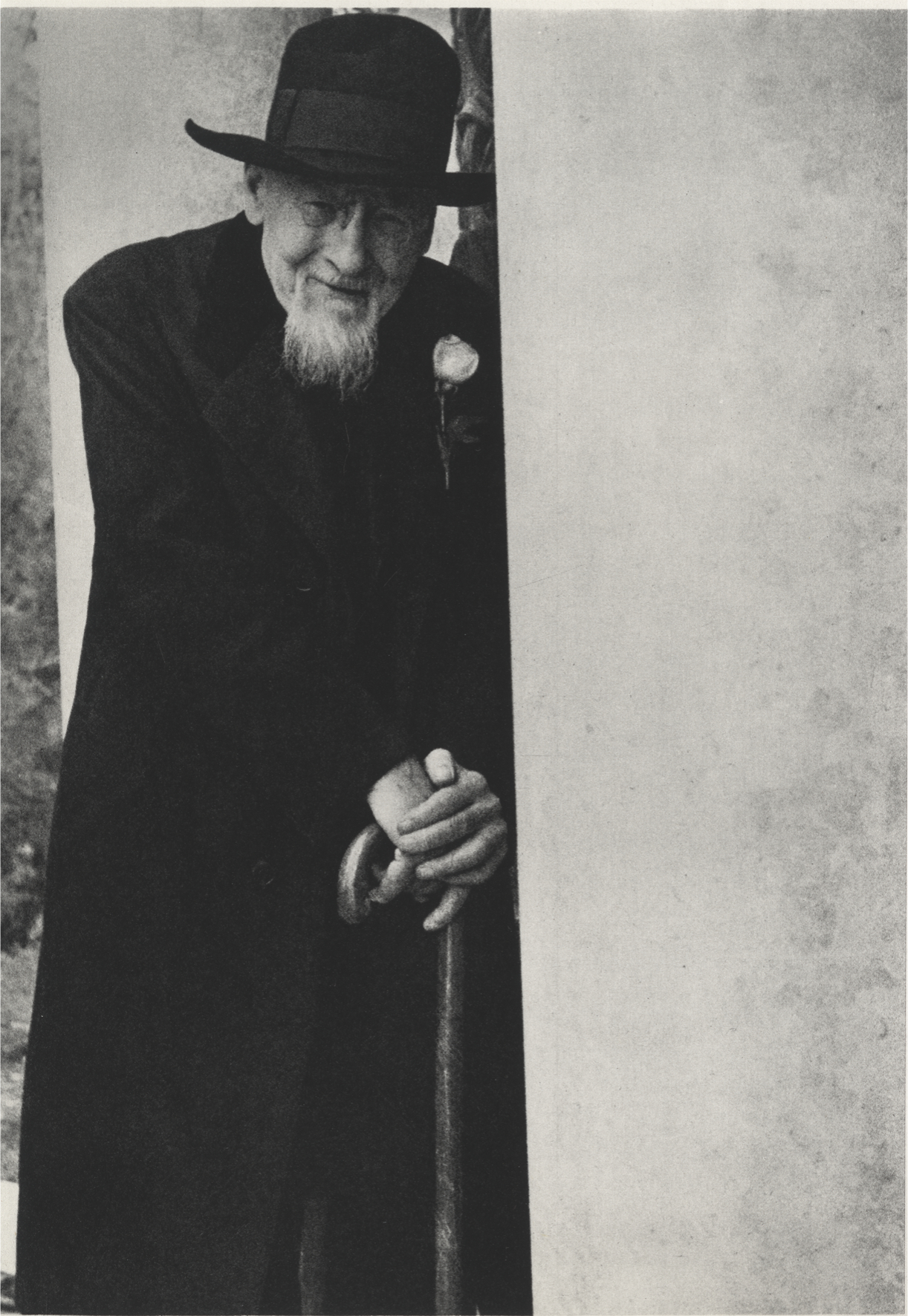

[8] Plečnik wore half-boots without laces (ankle-boots) called “štifletke”.

[9] Krečič, Plečnik in jaz / Plečnik and I, pp. 157–158.

[10] This chapter is summarised after the following literature: KREČIČ, Peter: Jože Plečnik – Ljubljana: DZS, 1992; KREČIČ, Peter: Jože Plečnik, moderni klasik / Jože Plečnik, A Modern Classic.– Ljubljana: DZS, 1999; PRELOVŠEK, Damjan: Plečnikova zbirka / The Plečnik Collection. – Ljubljana: Arhitekturni muzej (Museum of Architecture), 1974.

[11] Ravnikar, Jože Plečnik. Naši razgledi biweekly VI, No. 1 (120), 12. 1. 1957, p. 1.